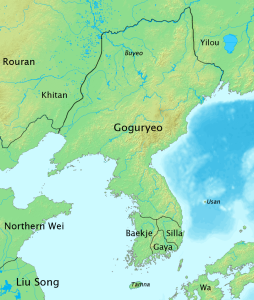

The wars between Baekje and Goguryeo’s King Gwanggaeto changed the power dynamics of the Korean peninsula. The Baekje-Wa-Gaya alliance was subdued, and Goguryeo’s ally of Silla was forced into an unfavorable situation vis a vis its supposed savior. King Gwanggaeto died in 413 at an early age, believed to be in his mid to late thirties. Unfortunately for Baekje, Gwanggaeto’s successor, King Jangsu, not only proved to be as competent a military leader as his father, he also lived to reign for about 78 years (his posthumous name “Jangsu” means “long life”). The shadow Goguryeo cast over the southern kingdoms was strongly felt.

Jangsu moved the Goguryeo capital to Pyeongyang in 427. This location put the seat of power much closer south, and this greatly unnerved Silla and Baekje. Although still allies with Goguryeo, Silla accepted Baekje’s offer of a treaty. The Silla-Baekje alliance would last for over a hundred years,and stipulated that if one of the countries was attacked by Goguryeo, the other would offer military help.

This alliance was drafted up by King Gaero’s father, and Gaero himself tried to bolster up as much help as possible when he gained power in 455. He sent his brother Gonji to live in the Wa courts of Japan to continue their relationship. He also sent emissaries to one of the Chinese kingdoms, Northern Wei. Northern Wei, however, had no intentions of antagonizing Goguryeo- in fact they were trying to improve relations with the country- and rejected the offer. Coupled with some internal power struggles between powerful clans, King Gaero had a tense political situation to deal with. And he would retreat from the hard struggles of politics with his favorite past time, baduk.

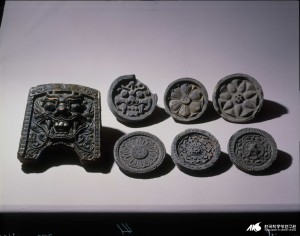

Baduk Stones. Source: Wikipedia

Baduk Stones. Source: Wikipedia

Baduk, or Weiqi, more commonly known by its Japanese name Go, is a strategy game where two players use black and white stones respectively, and try to control as much space on the board. It is to this day incredibly popular in most Asian countries. It is not an uncommon sight to see people surrounding two baduk players in a park in the afternoon. Korea in fact has a TV channel dedicated to the game.

Like most games of strategy, playing baduk at a high level creates a close bond in the players. You play a round in anticipation of their next move; they observe your behavior and enter your spirit to find any patterns. You create a trap perfectly suited for their temperament; they know you well enough that they can fool you into believing they walked into your trap. Combined with the fact that baduk games have a staggering amount of possible games, and a round of baduk can last for hours, this kind of double guessing and strategizing creates an intimate knowledge of yourself and your opponent. Deep and intense friendships arising from playing strategy games is a common motif in East Asian literature, and likely a common occurrence in real life as well. King Gaero found such a friend in an exiled Goguryeo monk named Dorim.

Gaero and Dorim during a game of baduk, from the Seoul Lantern Festival. Source

Dorim moved to Baekje after being exiled from Goguryeo. He was also a high ranking baduk player, and when he heard of the Baekje king’s passion for the game, approached Gaero and offered, in typical humility towards a monarch, his ‘meager skills’ to amuse and entertain the king. As an expert baduk player and a man of learning, Dorim was a perfect companion for the king. The two spent their days in discussion around the baduk board.

All this was a welcome island of peace around the tumultuous politics of Baekje. Dorim expressed how grateful he was that he, a foreigner, was so accepted by the King of Baekje. King Gaero expressed that his only regret was not meeting Dorim sooner. But this is not t say that he neglected his kingly duties either. One of the main topics the two discussed was how to improve the standing of Baekje. Dorim suggested that Baekje would strongly benefit from some internal construction, such as public works, the reconstruction of the palace, and the restoration of the former king’s tombs. King Gaero agreed, and ordered these projects be taken out. The Baekje capital of Wieryesong was absorbed in these works until the day Goguryeo troops arrived at the city walls.

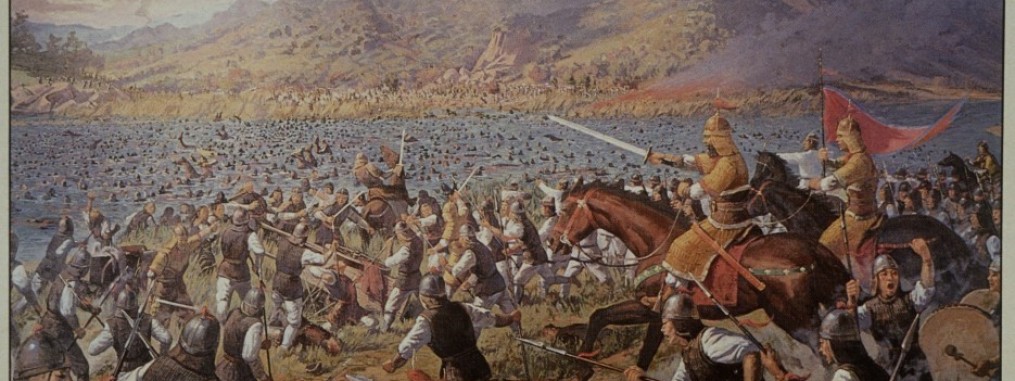

King Jangsu arrived at the Baekje capital with a force of 30,000 soldiers. It was an attack from both land and sea, an assault intending to crush the capital. Jangsu had things perfectly planned, he knew the best time to strike, and he seemed to know the best places to attack. It was as if he had knowledge of the city first hand. And the knowledge he did have came thanks to the information of his spy, Dorim.

King Jangsu had Dorim exiled on the charge of false crimes. Dorim worked to gain the trust and influence of King Gaero, gathering information to report back to Goguryeo. Playing strategy with Gaero also gave Dorim insight into the Baekje king’s mind. Dorim’s suggestion to keep the people busy in public works meant that the Goguryeo attack came as a complete surprise. King Jangsu’s spy gave him the decisive upper hand.

Gaero gravely lamented the situation. Despite his good intentions, his trust in Dorim had cost him his country. He rallied the troops and began preparations to defend against Goguryeo. He summoned his son, future king Munju, and told him “I will fight to the death to protect this country, but there is no use in you dying here too. Go, protect the royal lineage.” The prince fled to Silla to ask for help.

Goguryeo managed to invade the capital Wieryesong in 7 days. When King Gaero tried to escape, he was spotted by a Goguryeo general. Unluckily for the king, this general was a man named Jaejunggeollu, a former Baekje general who he had been exiled and defected to Goguryeo. Jaejunggeollu gave his former king first a deep bow, and then spat in his face three times. Gaero was taken as prisoner of war. The Silla reinforcements arrived too late, and Wieryesong was destroyed. Goguryeo now had control of the Han river area.

Baekje’s history is divided into three broad categories: the Wierye, Ungjin and Sabi periods. The Wierye period, which started in the early 1st century with Baekje’s founder King Onjo, ended in 477. King Gaero was executed the same year, having lost the war by the hands of a former subject and a former friend.

Where Wieryesong would have once stood. Source: Wikipedia.

A

A

A

A